Memorial, Universality, Freedom, and Our Sin

This Is Not an Internal Affair of the Russian Regime, But a Universal Case

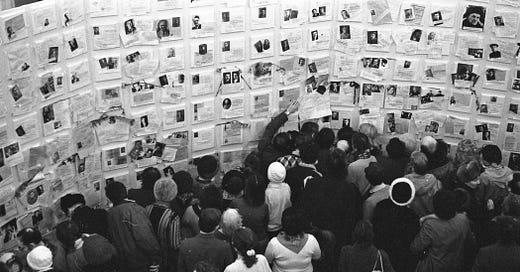

Wall of Sorrow on the victims of the Stalin’s Gulag at the first exhibition in the USSR about the crimes of Stalinism.

The first exhibition on the crimes of Stalinism, called “Week of Conscience,” was held thanks to Perestroika in November 1988 at the club of the Moscow electric lamp factory.

Picture : Dmitry Borko, November 19, 1988.

The “liquidation” of Memorial by the so-called Russian “justice” is an attack on the universal conscience.

Certainly, it was expected and follows the numerous persecutions against the organization co-founded by Andrei Sakharov and against its members. It comes in a context of increasing repression by Putin’s regime. Without being new, the control—when it is not the arrest, even the elimination—of those who contest the regime becomes almost general. Denouncing its crimes or the enrichment of its members often means risking one’s life, always one’s freedom.

Every day, in an increased and more visible way, an operation of rehabilitation of Stalin and denial of his mass crimes is deepening.

Every day, history is rewritten in order to deny the past crimes, but, even more, to prevent any investigation of the present ones.

This methodical destruction of the truth also goes hand in hand with the intensification of threats against the West and liberal democracies and the reinforcement of its ideological hold dedicated to the destruction of everything that is the basis of a free civilization.

This was the purpose of my two previous long papers on this blog: to show in which universe, which escapes any form of “normality”, the Russian regime intended not only to plunge and lock up the Russian society, but also the West. Let’s not think that we can separate the internal from the external: Putin wants to share with us the nightmare he imposes on his people. I did not think, to tell the truth, that I would return today to Putin’s Russia.

Killing universality

But I fear, reading some of the comments of personalities in the West or contemplating their overwhelming silence, that they have not understood the significance of the end, in Russia at least, of Memorial’s activities and the announced fate of its specific organization in charge of human rights and of the truth in the present—the Center for the Defense of Human Rights.

The liquidation of Memorial is not just another event in the repression committed by this regime and its absolute indignity. It has, if I may say, a founding significance, not only for Russia, but for the whole world. This founding significance is exactly a de-foundation. The word itself matters.

The suppression of Memorial corresponds in the order of history to what Putin’s war crimes are in the order of law: an attack on the very concept of universality, here in the domain of truth, there in the domain of justice. The link between the two is close: there is no truth without justice, nor justice without truth.

Abolishing Memorial would be the equivalent of liquidating, in the West, the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum and Memorial in Poland—which, by the way, concluded an agreement with Memorial before its liquidation—, the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC or the Shoah Memorial in Paris, the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe and the Jewish Museum in Berlin and, perhaps most importantly, as the French historian Cécile Vaissié pointed out in a striking article on Memorial, the archives in Arolsen (International Center on Nazi Persecution) and Ludwigsburg (Central office of the state justice administrations for the investigation of National Socialist crimes). The latter contain archives on deportees and on persons presumed guilty of crimes against humanity and war crimes, respectively. This is the purpose of a memorial, and of Memorial: to keep an up-to-date record of the victims and perpetrators and to bring new knowledge to light, because truth and justice—and this is also true in the present—presuppose that we know each other.

It is as if, in the United States, Europe, Canada, and all over the world, regimes were coming into being that punished with severe prison sentences all those who would expose the massive crimes committed by their state in dark times or by third states, or ordered them to say nothing and keep silent the names of their ancestors who disappeared in the abyss of mass crimes. It is as if the crimes of Nazism, Italian fascism, the Vichy regime in France, Belgian Rexism and the Walloon Legion, the Quisling regime in Norway, Spanish Francoism, the American slavers and the Ku Klux Klan, South African apartheid, Milošević, Mladić and Karadžić in former Yugoslavia, the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile or the Argentine generals, the Greek Colonels or the Rwandan Hutus, the Cambodian Khmer Rouge or the Turkish genocide against the Armenians, could no longer be spoken of.

It is as if a black sheet covers history forever.

The continuity of history for Putin is not only the forgetting of crimes, but more fundamentally the continuation of crime between yesterday and today. To the continuity of history under the sign of truth, Vladimir Putin opposes the continuity of history under the auspices of crime. It seeks to erase the black pages of past history to write those of today.

It is no coincidence that the People’s Republic of China intends to continue this silence on the crimes against humanity of Mao Zedong and those, subsequently, of Tiananmen Square, as well as in Tibet and Xinjiang. It is also known that revisionist and denialist attempts are being made in other countries, including Europe, by certain groups linked to the extreme right.

The significance of Putin’s enterprise is sufficiently well known and has been the subject of numerous papers in recent weeks. I will not go into detail here. But it is not certain that we have understood its full significance. This fact alone says a lot about the deep flaws of our strategy towards the criminal Russian regime. No doubt we are aware of the treatment that the Russian regime intends to give to the past, but we too often pretend that it is only the past. We continue to look away from what it says about our present and announces about our future. We disassociate the past from the present, as we do too often with our own history.

The destruction of a universal heritage

The history of Stalinism, like that of Nazism, Maoism and all the crimes against humanity committed throughout the world, does not belong only to the country where it took place. It is part of our common heritage. The crime against humanity, the war crime and the crime of genocide concern the whole of humanity and are not only the thing of the victims and the executioners. Auschwitz, the Gulag and Laogai are the bloody lands of humanity, not only of Germany, Russia and China. If they become only the limited heritage of a few, it will be doomed to destruction and oblivion.

Zakhor, remember!, is not only a cry and an injunction which, as a Jew, I can utter; it is actually our common phrase, whatever our legacy, which establishes universality as a community.

But it is precisely the very idea of this community, driven by the awareness of crimes and the necessary punishment they call for without any time limit, that Putin intends to destroy. There is a kind of continuity in the abomination between the mass graves of the Gulag and the torture rooms of the Lubyanka and the mass graves of Syria and the prison of Sednaya.

Stalinism is no more erasable from the history of Russia than it can be from the history of humanity.

There is certainly a factual reason for this: Stalin’s crimes against humanity did not only concern what is today the territory of Russia, but also the Baltic States, Poland, Ukraine—from the Holodomor to the deportation of the Crimean Tatars—, the former Czechoslovakia, etc. These are crimes without borders. But as crimes against humanity as such, they can have no borders. The work that Memorial has done and which is still far from being completed is ours, as is that of the Auschwitz Memorial and Museum and other institutions that are as much guardians of the past as of the present.

The crimes of the Russian regime are no more a “local” story today than they were in the past, again for reasons of fact and, dare I say it, geography, but even more importantly for reasons of principle. Perhaps this is also what the Western leaders have not understood—and they were slow to comprehend what the crimes of Nazism meant.

But Putin’s Russia has not yet had its Nuremberg.

Our historical fault

The fault of the West lies in this disconnection between the observation, which is far from new even if it has logically only increased, of Putin’s internal crimes and his external aggressions. But there is more: we have not understood what his war crimes, if not crimes against humanity, abroad say about his regime. Finally, no link has been made between these and the enterprise of destroying historical truth on the domestic level, of which the denial of the crimes of Stalinism constitutes the most significant part.

All in all, this enterprise of falsification was already underway at the end of the 2000s. I also remember that during my regular trips to Russia between 2006 and 2008, dissidents close to Memorial or simply trying on their own to dig into the history of persecutions and disappearances of their family members, were already telling me about the unambiguous warnings they received.

I have often pointed out the cognitive dissonance of some so-called international scholars: they fail to see the ideological continuum not only between domestic and foreign affairs, but also between propaganda narratives aimed at a domestic audience and those aimed at weak or corrupt minds—and sometimes both—abroad.

A large part of the West’s leaders did not want to see the same way as they did at the beginning, to take this example again, not want to take too much notice of the first information they received, in the middle of the Second World War, about the existence of the Nazi extermination camps and what was going on there.

Here again, there are two reasons. The first was superbly stated by former Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves in his speech in early October 2021 in honor of Alexei Navalny: “To truly honor Navalny, we instead must confront the stench of our own liberal democratic West. That stench swirls from our own corrupt politicians and political parties, from our naive and greedy governments, and even the most prestigious, centuries-old universities. It swirls from businesses who prize profit over justice, truth and freedom. It swirls from bankers, lawyers and accountants who launder money and reputations. It is this corruption, our corruption, that aids, abets and sustains, indeed nourishes the murderous looting of the Kremlin’s boyars and their minions as well as other odious regimes around the globe.”

The persecution of Memorial and its liquidation as well as the persecution of the opponents of Putin’s regime—we know that it can mean their murder—are the result also of this corruption of the West. It is also the result of the passivity of these same Western governments towards this corruption and their refusal to punish it and make it a crime of treason. It is the result of the policy of those half-skilled people of whom Pascal spoke, who think that it is always necessary to have a moderate position, in between, always “open” towards Putin’s Russia and other criminal regimes. This is the result of the lack of strict selection of those who speak in the ears of our princes and who may have other interests. It is the result, when it is not corruption, of our perverted and, ultimately, abolished intelligence.

And tomorrow, in spite of Memorial, some people will continue to rush to the Kremlin organs, to negotiate, to discuss, to smile, to shake hands, to give hugs, to continue to talk about culture, health and the environment, as if nothing had happened. And Memorial will remain closed and its activists persecuted or forced into exile.

And we will have forgotten, just as we have forgotten the crime.

For there is a second reason at the heart of our fault: we do not understand. We do not understand what it means to deny crimes against humanity because it is not in our country that this happens. We are reassured because we have, at least in some European countries, laws that penalize Holocaust denial. Incidentally, as far as I know, we have none or hardly any for Stalinism and other crimes against humanity. We have even less against the worst crime of the 21st century: those committed by Assad, but also precisely by Putin and Iran, in Syria. So we feel somehow protected and we do not perceive that the Russian regime’s denial of the crimes of Stalinism has a concrete significance, not for the past, but for the present—our present.

In short, Russian revisionism becomes or remains an internal history. And for many of our Western political leaders, Russian internal histories remain internal by definition, whereas they are anything but precisely internal, any more than the Holocaust and, before the racial laws or Kristallnacht, were internal affairs of Nazi Germany.

I spoke earlier of the universality of historical consciousness. What is at stake here is also the universality of freedom, the first object of our renunciation.

We have not understood precisely that freedom could not exist without truth, and first of all historical truth. We think that we can be free by going about our daily business, worrying little about history. We think that we can forget or not know Sakharov or the White Rose; we think that it is not a big deal that Stalinism or the Holocaust are being forgotten—and surveys in many Western countries show that this is happening—; we think that the so-called glory of the victors counts more than Cato’s plea for the vanquished; we think that commemoration is enough to keep us going while we turn away from the crimes of the present.

Finally, in their insignificant mediocrity, perhaps this is what some European leaders have anticipated by not lifting a finger or by containing themselves to express their “deep concern”. In the end, Putin’s destruction of the past is only the announcement of what will happen in our societies.

Putin, Xi Jinping and the others have already won because they have perceived that our society no longer has the love of truth as a bulwark.

The conditions of freedom

“For their freedom and for ours” is the slogan that those who denounce the destruction of fundamental rights in dictatorships often use—and rightly so. It echoes the inspiring words of Pastor Martin Niemöller. In fact, when they came after Memorial, we said nothing—or very little. And tomorrow? We know only too well what will happen next. We in the West have delegated the fight for freedom to the dissidents and demonstrators in Russia, Belarus, Hong Kong, Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, etc. In the same way, we have delegated the concrete and physical fight for the freedom of Europe to the Ukrainian fighters. We are in this world of delegation and many in the West do not even know about this delegation. We think that our freedom will remain unharmed and we believe that the abolition of other people’s freedom does not threaten our own. Or, even worse, we have become incapable of perceiving the logic that drives those who destroy it.

In matters of historical consciousness, of right and freedom, it is this same universality that we refuse to perceive. Perhaps it is because we do not care that much about freedom. We perceive its meaning only in a distant way—as in the case of those distant wars that have ceased to be ours. I don’t know where the chicken and the egg lie, but there seems to be a direct correlation between the remoteness of the present consciousness of history and the remoteness of freedom. What is left of freedom when the scope of crime is minimized? Or do we accept it as long as it is committed apparently far from us? Or is crime no longer the object of our conscience, but confined to its edge as to that of history? Or do we pretend to deal with “geopolitics” and “relations between States” without either crime or history being likely to feed our action?

The “liquidation”—since that was the word used—of Memorial brings us back to these urgent questions. It obliges us to do so because it is a symbol—that of the link between the memory of crime, historical consciousness and freedom—but also because it was the work of men and women of unspeakable courage and absolute prescience, who know that history must be defended in the present in order to prevent other men, women and children from falling back into the whirlpool of a mad power that, in the words of Hannah Arendt, declares their existence superfluous.