Tbilisi, Georgia, September 1, 2024. Photo: Nicolas Tenzer

Many strategic analysts, not to mention Western capitals, regard Georgia with a mixture of indifference and embarrassment. Indifference, at least relative, because it’s a country of less than four million inhabitants which, even if it’s located at a strategically sensitive crossroads— it borders the Black Sea; Russia, which has effectively annexed two of its regions since 2008; it adjoins two countries at war, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey—is not a decisive control point. Embarrassment, because the non-intervention of the democracies in the 2008 war, preceded the same year by a Franco-German veto for its NATO membership action plan, remains a major stain on the Alliance’s credibility.

Allowing Tbilisi to fall into the Russian orbit in the context of the all-out war against Ukraine would be a highly significant sign of abandonment at a time when the Allies have, in fact, already failed Kyiv.

Ambiguous but already obsolete perspectives

The attitude of Westerners, particularly Europeans, is further complicated by several external factors.

Firstly, while candidate status has been granted to Georgia at the end of 2023, this gesture towards the Georgian people, not the government, is anything but a firm commitment. Not only does it depend on the policy followed in the years to come—the continued control of the Georgian Dream (GD), in other words the Kremlin, over the country ruling out any European destiny—but no one believes that Georgia will join the EU for at least ten or fifteen years. Indeed, some European leaders are skeptical about this possibility, given the change in mentality required.

Secondly, we can’t pretend, as we did with Ukraine, that Georgia isn’t an occupied country virtually at war. Is it possible to integrate Tbilisi into the EU without resolving the question of Abkhazia and South Ossetia? Even if we can envisage provisional institutional solutions, facilitated by the European legal framework as I have already mentioned, it seems impossible to envisage integration as long as Russian troops occupy these regions. Nor can we accept the status quo when all democratic countries, and even a few others, have never recognized these two puppet republics. Indeed, one of two things could happen: either—if the conflict remains unresolved—this could justify the invocation of Article 47-2 of the EU Treaty (which the Allies would rule out a priori), or—if the Allies accept the fait accompli—this would mean that the EU would in a way be enshrining in law the acceptance of Russian domination and of the result of a coup de force more than 16 years old. This temptation of some Allies already exist for Ukraine.

What this would mean is all too clear. The EU easily allows for a third way: integration of Georgia as it is, with a promise to integrate the two captured regions as soon as they have been liberated; no direct action in the reconquest operation, but security guarantees for the free areas—it’s up to each and every one of us to assess the value of these. The problem is, as we shall see, that even this rather cowardly scenario may not be possible today.

Finally, there is a global strategic dimension to the prospect of EU membership. If this were to happen, it would a priori be following the accession of Ukraine and Moldova. The dimension of “liberation” from Russian domination would apply in all three cases. Above all, it would reflect a concerted strategy on the part of the democratic powers, particularly Europe, the coherence of which is far from apparent today. What’s more, there can be no simple integration into the European Union without, at the same time, membership of NATO. As with other future enlargements, the two go hand in hand. Thus, the almost simultaneous nature of such a double membership applies to countries such as Ukraine, Moldova and, one day, Belarus—logically, integration into the defense organization, which is easier, should come first.

Yet it is striking that, for some time now, the Allies have stopped expressing an opinion on the Georgian case, even though the refusal to grant a MAP to Kyiv and Tbilisi in April 2008 at the Bucharest summit was the permissive factor in Russian aggression.

The liberal democracies therefore need to adopt a coherent policy towards Georgia, but this also requires a common strategy in the shorter term, depending on how the elections are conducted and their results proclaimed.

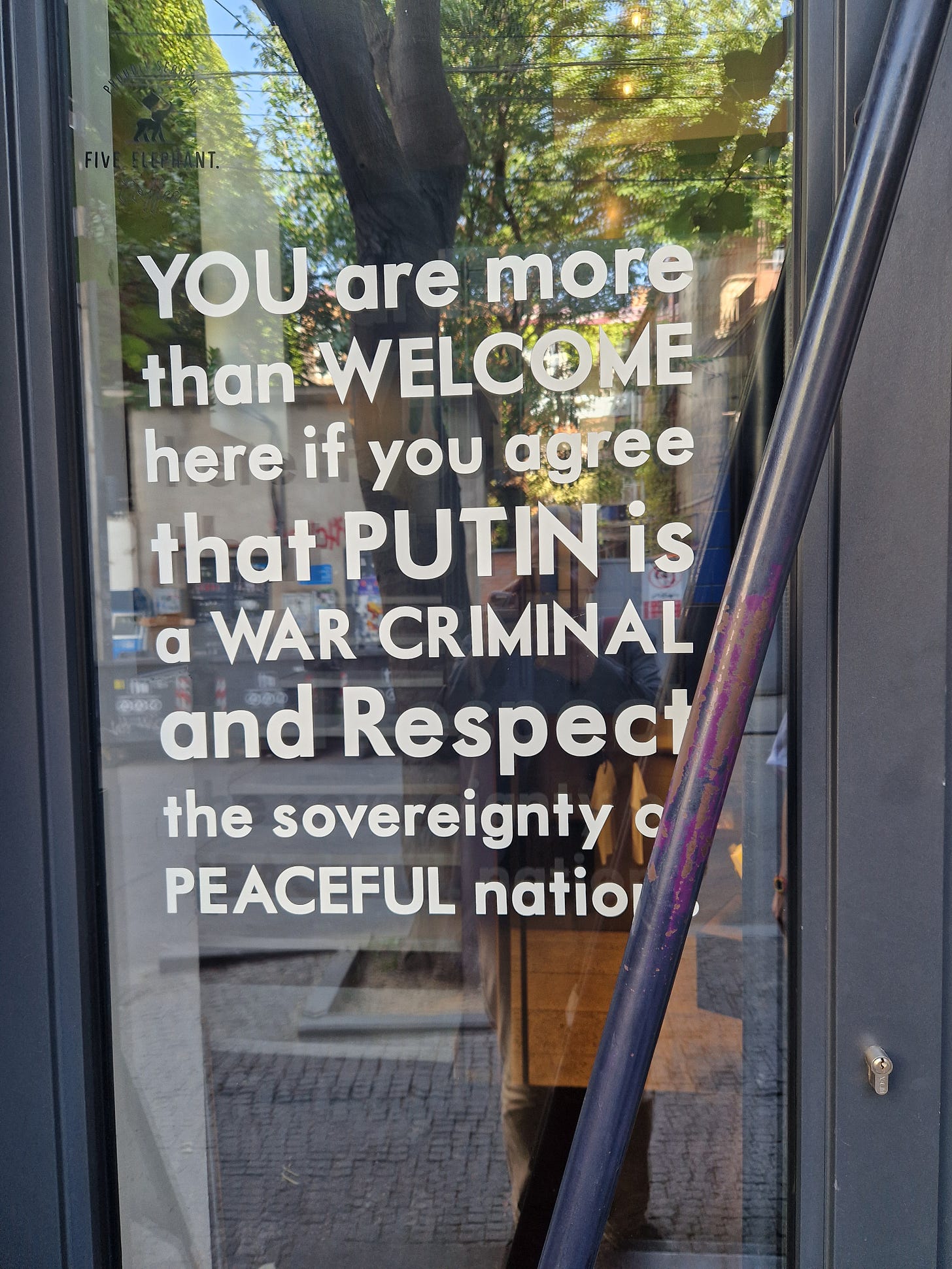

Coffee- and Book-shop in Tbilisi, Georgia, September 1, 2024. Photo: Nicolas Tenzer

Increased Russian control

Russian control over Georgia is nothing new. However, the situation is worsening month by month. More than a year ago, I recalled here the factors that led to the conclusion of the existence of a captured state. I won’t repeat my analysis of Russia’s multifaceted influence, which unfortunately remains entirely relevant today. Since then, as I was able to see again on site in September this year, the situation has only worsened: a Parliament dominated by the GD and its allies voted in the scurrilous law on foreign agents, rightly dubbed the “Russian law”; direct flights between Tbilisi and Moscow resumed in March, a telling symbol when Georgia was the destination of choice for Russians fleeing enlistment in the army, but no doubt also for others; a law was voted in which the rights of LGBTQ+ people were undermined, major attacks on members of the opposition (arrests, searches, beatings) and damage to their property, direct and undisguised threats to political pluralism should the GD win the parliamentary elections, including a ban on opposition political parties, as announced by Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze. A palpable desire to bring the country to heel. In the days leading up to the legislative elections on October 26, this threat became more acute.

Not surprisingly, one of the world’s leading investigative journalists has just shown that Russian services have already “proposed” to the Georgian Dream, which is now in a very small minority in the polls, to overturn the vote. A few days ago, among other entities, the Central Electoral Commission was “hacked”, giving Moscow, and therefore the Georgian services, all the necessary information on voters. When I say “offered”, I naturally mean “demanded”. The reality is that Moscow gives orders to Bidzina Ivanishvili and his henchmen, and that the oligarch and the GD hierarchs and elected representatives willingly obey them. Some in Georgia were talking about Putin’s pressure and threats to Ivanishvili, which made him foresee his fate and that of his family if he didn’t comply. Perhaps even this “urgent advice” is useless. An investigation also recently showed, unsurprisingly, that despite his denials, he had retained activities in Russia.

So we need to be perfectly clear about what “reversing” the vote would mean in practice. A recent example of this is Venezuela, where the massive results in favor of the opposition to the dictator and criminal Nicolás Maduro were immediately denied and “replaced” by results given by the government. These results were only recognized by Russia, China, Iran, Syria, Cuba, Bolivia and Nicaragua—in short, by no democratic country. But beyond their protests, there was no resolute action against the “Bolivarian” regime. The fraud was so massive that even the Western “tankist” parties, reluctant to condemn the massive bloody repression in this country, failed this time to congratulate the dictator. A scenario of this type, where the real results are immediately “erased” by the powers that be and replaced by more fanciful ones, is perfectly possible in Georgia. This practice can certainly be combined with other common practices: vote-buying, which has often been seen in the past, electoral fraud, intimidation, falsification of diaspora votes, and attempts to prevent the work of international observers.

Of course, no one will be fooled by this falsification operation, first and foremost the observers, who will report on it in their reports, and the democratic leaders. If this were to happen, it's a safe bet that, on the same evening, not only would the opposition proclaim the real results—as was also the case in Venezuela—but they would also declare victory, affirming their determination to pursue the path of Euro-Atlantic integration and immediately repeal the GD’s freedom-killing laws. Faced with the government’s fraudulent proclamation to the contrary, the Georgian people will immediately take to the streets en masse, and the Georgian president will demand that the real results be respected.

This is where the scenario could become most terrifying. Of course, it’s always possible that the worst won’t happen, and things don’t always turn out as planned or announced, feared or wished, but we have to be fully aware of the worst—it’s never the worst, in any case, that will make the Russians back down. It’s doubtful that the Georgian Dream will either.

Salome Zourabichvili, president of Georgia, and the author, Tbilisi, Georgia, September 2, 2024. Photo: All Rights Reserved

The test of violence

When it is said that Moscow will do anything to keep Georgia under its boot, we have to see what this “anything” means. Firstly, anti-government protests will be increasingly severely repressed. Certainly, they have already been—with beatings, severe assaults even resulting in death in one case three year ago, multiple arrests, etc.—but the Georgian people have shown that they are not prepared to accept this. The Georgian people have demonstrated that they will not be cowed or intimidated by repression, and they will continue to do so. However, this is when the government, ready to do anything to please the Kremlin, could use the hard way, with the assistance of the Russian services increasingly present in Georgia, to prevent any protests this time: firing live ammunition at demonstrators with the intention of killing them, as the Yanukovych regime’s Berkut did during Maïdan in 2014, or Lukashenka’s omon in Belarus in 2020. Faced with special forces ready for anything, what will the opposition be able to do? Will it be able to take the main seats of power, but at what cost and for what prospect?

It is also likely that, in the meantime and at the same time, the main opposition leaders will be arrested, along with the most visible and well-known activists, and their offices and homes occupied by the special forces. The threats against the families of these figures will become ever more precise and direct. In any case, this is a scenario without limits or the slightest restriction, since the orders given by Moscow leave no room for interpretation. In the present case, they are clear: Tbilisi’s desire to tie in with the West must be stopped. The government might then be tempted to declare a state of siege and proclaim martial law. Or, citing the existence of a “conspiracy” of “anti-Georgian forces activated by the CIA”, it could ask for the “peaceful” assistance of a “great ally”, Russia, to confront this “subversion of national values from outside”. No one will be fooled, of course, but it’s clear to see that this could prefigure the occupation not just of 20%, as since 2008, but of 100% of Georgian territory.

No doubt it won’t be a military “invasion” with heavy weaponry, as it was then. In fact, it would be difficult for them to distract forces already occupied in Ukraine and often in a difficult situation. The Russians, incidentally, will have no need of this: with the help of local satrapies, a few well-positioned special forces can thwart any hint of rebellion. The Georgian people will certainly continue to carry out, here and there, actions of resistance and rebellion, perhaps targeted attacks against those close to power, giving way to more repression each time, but it is far from certain that this movement of harassment of the occupier and his local collaborators will be able to radically change things on a country-wide scale.

Some are already anticipating possible responses from the European Union and the United States. Their arsenal is well known: targeted economic sanctions and travel bans for Ivanishvili, members of the government and the leaders and parliamentarians of the Georgian Dream, seizure of their assets, export bans and red-listing of companies in complicity with these people, and, more generally, reintroduction of visas, notably for entry into the EU—with, of course, facilities for opposition figures or those persecuted for political reasons. Withdrawal of other nationalities obtained by those in power is also a serious option, as is the withdrawal of foreign awards—the case of Ivanishvili is often cited, who also has French nationality and in 2021 was awarded the Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest decoration. However, once Russia’s will has been expressed, there is little chance that these measures specifically targeting Georgian personalities will change the situation.

The only effective prospect would be counter-action in support of the Georgian people, to thwart that of the Russian intelligence services. The problem is, however, that Western intelligence have long since lost the habit of such actions and counter-actions, and that while they have learned, albeit insufficiently, about cyber threats, disinformation, terrorism and sabotage, it is not or no longer part of their culture to act on a large scale, with potentially heavy defensive means that are also offensive, to counter an action of foreign subversion operated on a large scale. The Russians know this too. We won’t even mention here the option of heavy military action, which was already ruled out in 2008, even though it would have been both possible and desirable, given that it involved direct military aggression and that Moscow was much less powerful than it has become today.

A path to emancipation

The Georgian elections are in no way a test for Georgian society, the vast majority of whom, not only in Tbilisi, know perfectly well that their Euro-Atlantic destiny is the only possible path to freedom and prosperity. They are not fooled by the government’s propaganda claiming that the GD is the “party of peace”—by which is meant submission to Russia. The argument that it was safer not to take sides in Russia’s war on Ukraine is also a minority argument. Above all, it conceals the current danger: that of a programmed submission by Georgia’s GD to Russian power, which somehow intends to finish the job it started. In short, it cannot be said that the majority of the Georgian people do not know what they want. Some may have been misled in the past by the GD’s double talk, which on the one hand affirmed its commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration, and on the other did everything in its power to hinder it. Ivanishvili is constantly repeating the Kremlin’s narrative that the Georgian authorities of the time were responsible for the events of 2008. As long ago as last year, former Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili, who became President of the GD again in February 2024, blamed NATO for Russia’s war against Ukraine. No one in Georgia is unaware of the government’s intention: to turn Georgia into a Russian colony, subject to the same iron repression in the name of traditional values and Orthodoxy. This would mean an even sharper increase in the exile of young Georgians, which has been growing steadily in recent years, with many seeing their country as the next no-future.

The test, on the other hand, is for the democratic West. It has a lot to apologize for: its inaction in 2008 in Georgia, in 2014 in Ukraine, in 2013, 2015 and beyond in Syria. To give hope to Georgian society—and for this reason alone, since the political conditions were certainly not ripe—the European Union granted Tbilisi candidate country status in 2023. This was enough for Putin to instruct the Georgian government to give every signal to the contrary. The EU found itself at an impasse and didn’t know how to react. It was certainly not helped by Enlargement Commissioner Laszlo Trocsanyi, Viktor Orbán’s former Justice Minister, who may not have had much inclination to confront a pro-Russian power. The interim period, during which Ursula von der Leyen was campaigning for re-election, was not conducive to a strong reaction, and it is no coincidence that the most serious breaches of the rule of law (notably the Foreign Agents Act) occurred at this time. Of course, Russia’s war against Ukraine has taken Georgia somewhat out of the spotlight—the Middle East conflict even more so. Yet the fate of Ukraine, Georgia, Belarus and Moldova, as well as Armenia, are intrinsically linked.

Some European leaders have expressed their “deep concern” at the violation of Europe’s fundamental principles, increased repression and estrangement from the EU, but without going beyond empty words. Both because this is not its modus operandi and because it does not know how to act—and knows that Washington is more concerned about Georgia in Atlanta than in Tbilisi—it has not prepared any severe retaliatory measures. We can’t see the United States going any further, regardless of the American electoral context.

The Georgian people can therefore only count on themselves, on their ability to resist Russian domination through small, everyday acts of resistance and a return to the protective reflexes they had during the period of Soviet domination and oppression. All too often, we forget the heavy toll that the Georgian population, and intellectuals in particular, paid during these dark times. In Tbilisi, a number of places recall these forgotten and sometimes desperate battles. Likewise, there is an ongoing struggle to resurrect from the depths of historical memory the genocide committed by the Russians in Abkhazia in 1993 against ethnic Georgians.

With this memory of death, struggle and treachery in mind, we can only view the coming months with the deepest anxiety. Just as Putin will never stop his war in Ukraine unless he is stopped and radically defeated, so he will never relinquish his stranglehold on Georgia. All the indications are that he believes the time is ripe. So he won’t give up. Perhaps, tragically, for Georgia, the only hope now will come precisely from the crushing, indispensable Russian defeat in Ukraine. I have often written that, ultimately, its fate will depend on this. But this does not absolve the Western democracies from going much further in their confrontation with Moscow should the possible events I have mentioned occur.

No one can claim not to have been warned. But are warnings still useful today?